Everything you wanted to know about embryo research but were too afraid to ask

This week: Artificial wombs and synthetic embryos

Hey it’s Alex. Every so often, I’ll tackle an ethical issue in biotech suggested by a reader. I’m really excited about this one! Do you want to hear more about something in particular? Get in touch! And as usual, feel free to forward this to anyone who might dig it.

There are three overlapping news stories this week that are all about embryos. 👏

Join me on an exploration of the ethical and legal concerns at play, and why we should update the laws!

In the first news item, an Israeli team announced that they have successfully kept mouse embryos alive in artificial wombs (spinning glass jars full of nutrients) long enough for limbs and organs to form.

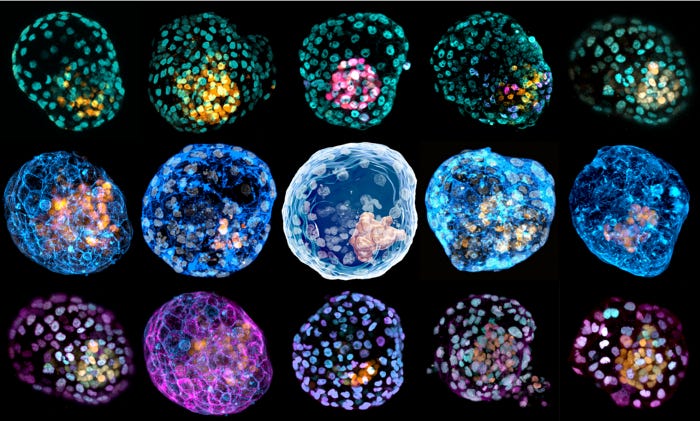

Next, two teams announced the existence of synthetic “human blastoids,” which mimic human embryos in many ways. In Future Human, Emily Mullin reports that the blastoids will help scientists “study the causes of birth defects and genetic diseases, as well as the impact of chemicals, toxins, and viruses on early embryos.”

And lastly, I wrote two weeks ago about efforts to extend the 14 day rule on culturing human embryos, the history of which you can read about here. The MIT Technology Review reports that the International Society for Stem Cell Research is the latest—and most influential—group to support this effort. It’s a calculated move, to be sure, but it’s the right one at the right time.

During the Trump administration, the scientific world sat on its hands. There was little point in advocating for renewed attention on embryo research regulations. (Some of us did it anyway.) But now, with a renewed respect for the importance of discovery in the life sciences, plus the recent major leaps in embryo research, there couldn’t be a more perfect opportunity to make the case to consider changing the rules.

Why is embryo research important?

The human fetus is a black box in the first days and weeks of development, when it’s an embryo. While we’ve certainly come a long way recently, there is so much we don’t know that could be useful information for people who gestate, for people who are unable to have genetic children due to unsolved fertility mysteries, and for patient advocacy groups who want more information and potential cures for rare diseases.

In the first few phases of fetal development, cells that will soon become organs begin to form. This is also when many diseases develop, as well as when many miscarriages occur—most for unknown reasons. Studying what happens to an embryo before becoming a person can give us incredible knowledge about how genetic and environmental factors contribute to health and disease and where and how these factors come into play.

Personally, I really want to know more about how the fetus interacts with the placenta, a totally unique organ.

For all you futurists reading this, when coupled with tools such as artificial wombs, this research could lead us toward the controversial place where a body is not needed to gestate humans. Yeah, it’s freaky! But it also creates opportunities for families where neither parent is able to carry children. It could be a life saver for preemies. It opens doors for the future of space research and off-earth living. It has even been suggested that ectogenesis could be a feminist advancement—although there’s a lot of debate about that.

What’s the challenge to opening up US embryo research?

There are a few hurdles to get over for embryo research to kick off in earnest.

First is the absolute shitshow of the US’s regulatory infrastructure. Yes, it’s still technically illegal to do research that destroys embryos with federal funding. Every year since 1996, the Dickey-Wicker Amendment is renewed in the Congressional appropriations bill, and no one bats an eye.

In response, states have taken it upon themselves to fund some of this research, creating a chaotic patchwork of regulations that can vary dramatically. (Take a look at this insanely complicated chart.)

The federal ban has also resulted in a scarcity of embryos and fetal tissue that can be used for research. If you can’t create them and you can’t destroy them and you can’t use the ones other people don’t want, where do the embryos come from? (Mostly they come from non-human animals, but their usefulness is limited.)

But what about these new “embryo-like” structures? They’re not technically embryos, right? And what about embryos made with adult cells that have been reprogrammed into gametes? And then what about trying to grow those in artificial wombs?

Scientists are justifiably confused (and so am I, let’s be honest) about what can get funding and what can’t, and what’s allowed to be destroyed and what isn’t. At the moment, this major science can only be supported by private funders, or NGOs.

Besides funding and regulatory confusion, though, there are a number of ethical concerns about synthetic embryos, artificial wombs, and even expanding (or not) embryo research.

Some of these include editing embryos for particular traits, and the potential for misuse of the technology. But overall, embryo research is seen by medical experts as an ethical enterprise. This statement by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine lays out the many reasons why.

So what’s next? Change the rules

I am frustrated that the pro-science progressive left hasn’t taken up embryo research as a cause célèbre, considering the potential benefits.

On the other hand, I do understand the left’s hesitancy. There is a fear that smudging the well-worn lines around embryo politics and adjacent science could incentivize reckless and unethical experimentation, which makes strident social justice warriors uneasy. Are researchers and fertility doctors taking bioethics courses? Will they be forced to reckon with the Doctrine of Double Effect or similar philosophical principles related to work that wields a double-edged sword? Certainly in this time of capitalism run amok and the rise in white supremacy in the West, easing the rules on embryo research without public input and sensible new regulations in place could have a disastrous impact, widening the economic and genetic divide between the haves and have-nots.

Down the road, it’s also possible that moral claims connected to the abortion debate could become incredibly tenuous when you put ectogenesis on the table. For the left, as Glenn Cohen points out, the argument in favor of a right to abortion (the right of a person to stop gestating) becomes a lot more difficult, politically and legally, if it’s possible to sustain the fetus by transferring it to an artificial womb. It could also change the definition of viability.

I get why progressives don’t want to wade into this conversation. It’s a tough one!

However. My stance is, and has always been, that it is imperative that reasonable people who support the advancement of science educate themselves on the issues. Literacy leads to good policy and mainstream debate can lead to progress.

Thanks for reading!